I have been out of town, working, & applying for jobs so haven't had much time to write creatively :(. here is a paper i wrote for my history of modern art class in 2016, maybe my fave thing i wrote in college. if i were to go to grad school, i'd want to study something like this

As modern art hurled itself into the 20th century, it developed parallel to the rise of mass culture. With these two separate conventions evolving beside each other, and with mass culture becoming increasingly consumed in place of modern art, art began to settle within the margins of society, provoking experimentation which centered around abstraction. What once made modern art visually radical and unprecedented in the 1860s and 1870s became “a banal and established part of the bourgeoisie” (Clark 258) in the later 19th and early 20th centuries. As modernity matured and mass culture grew, everyday behaviors and entertainments no longer operated as a feeling that could be represented simply with paint and canvas.

The work of the early modernists (for the purposes of this paper, consider them defined as specifically artists who made work between 1848-1870) primarily centered around portraying physical, visual embodiments of modernity. Monet and Caillebotte’s Hausmannized landscapes, depicting new steel girders of the Gare Saint Lazare, and the obtuse trusses of the Pont de l’Europe, conveyed modernity occupying undeniable physical space. Manet, Renoir, and Degas’s illustrations of personal landscapes, in which figures stood in as representative types for newfound social implications in early-modernized Paris. Common behaviors which were popular subject matters for most early modernists included leisurely visits to the Parisian suburbs, walks along the shining Hausmannized boulevards, and ogling technologies. However, as modernity ripened, and mass culture began to slowly rear its head, artworks began to concentrate around one specific site of visual culture: the cafés-concerts.

The cafés-concerts were not sites of mass culture; they were sites of popular culture. Mass culture is defined by “mass”; viz a loss of individuality (i.e. “mass” production). Popular culture derives its meaning from the truest sense of the word “popular”, i.e. speaking for the people. As Kracauer (68) stated so astutely “the masses…[are] not the same as the people”. The performance style and manner of showcasing of spectacle at the cafés-concerts fostered, more than anything, interactions and confrontations between social classes. As Clark (238) said, the café-concert “mitigated these instabilities by making a spectacle of them”. Thus, popular culture still retained representability with the modernists because it remained an archetypal, easily paintable site of modernity. The cafés-concerts however, also marked a jumping off point in the rise of mass culture, as they were a modern hobby which physically centered itself around spectacle, but was not defined by it. As Clark (210) said “They were cafés, not theatres”. Mass culture can be defined by the transition of spectacle from a sideshow to the center of the interaction.

The work which most principally and famously illustrates the cafés-concerts was Manet’s Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère. Painted in 1882, it portrays a listless young barmaid presumably working at a popular café-concert, mid-interaction with a bourgeoisie customer who is reflected in a frosty, seemingly impossible mirror. The spatial organization of the work is difficult to make sense of, as all the information given to the viewer about the scene is conveyed through the reflection in the mirror. The positioning puts the viewer in the shoes of the bourgeois, who appears to be buying something (although as to what it is uncertain, as prostitution was more than common in the cafés-concerts). Manet epitomizes an exchange of capital as a site of modernity in this picture. The figures in this work, once again, follow the early modernist tendency to utilize portraits as representative social class types. This interaction in the Folies-Bergère, in the cafés-concerts, were singled out as simple representations of modernity because they were sites of popular culture which remained simultaneously individualized and classified, thus easily depicted in the same manner which was previously effective in early modernism.

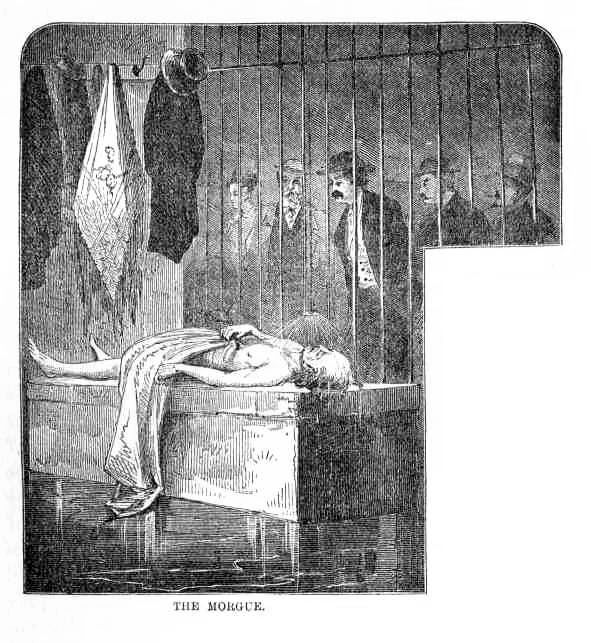

Further into the 19th century, and into the early 20th, spectacle and mass culture transformed itself into a preposterous, all-consuming cultural affair. Day-to-day hobbies became increasingly morbid and absurd. Popular Parisian attractions in the 1880s-90s included the Paris Morgue, which, as detailed in Schwartz (90), began as a depository for the anonymous dead, and turned into a full-scale “visual auxiliary to the newspaper” and “show”, where spectators could come to see the dead who had been sensationalized and immortalized in the Parisian non-partisan press.

Cafés-concerts began to transition into music halls, where the lights were kept off and the performances became simply masses of bodies in motion on a stage. The neo-impressionist Seurat tried his best at representing this digression in 1890, with his work Le Chahut. The painting is among the only works which attempt to put a direct visual representation to mass culture. The physical appearance as well as spatial relationships are defined by Seurat’s chromoluminarism, which give the work an incredibly unique way of portraying a dark room, casting a glowing sheen on the forms. Seurat’s technical capability with this work alone sets it apart from other attempted representations of mass-culture, as it gives a depiction of a dark room a new depth. The scene Seurat chose in Le Chahut is the climax of a can-can, a dance characterized by the performers’ ability to carry out mechanical motions in sync with one another. Performers of the can-can “are no longer individual girls, but indissoluble female units whose movements are mathematical demonstrations” (Kracauer, 67). Seurat does his best to represent this machine-like physicality, by attempting to depict perfect visual balance. Two men and two women stand on a stage in the dance hall, illuminated by gas light, their legs extended in “erotic parentheses” (Crow, 281), all reduced to mere physicality and mass for the pleasure of the pig-like spectators, who Seurat positions below. Le Chahut is dramatic, grotesque, and unpleasant; a huge movement away from the manner of representing nightlife which dominated just 15 years earlier.

The artworks which arose in the late 19th and early 20th centuries continued to transform, abandoning stylistic modernism, and favoring abstraction. The rise of mass culture played a major role in this movement, as it made every day subject matters, which were once extremely popular with impressionists and early modernists, appear grotesque and banal. Mass culture and modern art became antitheses of each other, mass culture forcing modern art to occupy the periphery of society. It developed into a sort of cyclical motion, in which mass culture evolved to be increasingly unrepresentable, and those who absorbed mass culture became increasingly removed from art.

WORKS CITED

Clark, TJ. “A Bar at the Folies-Bergère.” The Painting of Modern Life (1984): 205-258.

Kracauer, Siegfried. “The Mass Ornament.”New German Critique (1975): 67-76.

Crow, Thomas. “Mass Culture and Utopia: Seurat and Neoimpressionism.” Nineteenth Century Art : A Critical History (2011): 274-287.

Schwartz, Vanessa R. "Cinematic spectatorship before the apparatus: the public taste for reality in fin-de-siècle Paris." Cinema and the invention of modern life (1995): 297-319.

Ty to Professor Danny Marcus for teaching me this